The Bitcoin White Paper is one of the most famous technical papers in the world. Its language and ideas have been meticulously studied ever since it came out on October 31, 2008. Among the reasons for that is to look for any clues as to who the real identity behind its pseudonymous author, Satoshi Nakamoto, might be.

By background, it is known that Satoshi claimed to have written all the code first and then wrote the paper afterwards. “I actually did this kind of backwards. I had to write all the code before I could convince myself that I could solve every problem, then I wrote the paper,” he said in an email to Hal Finney on November 9, 2008, 10 days after it came out.

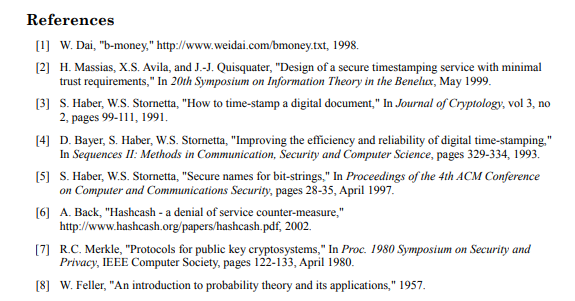

There’s only eight total references in the References section, one of which lists a paper authored by Adam Back who Satoshi emailed in August 2008 before the paper’s release and another is a paper by Wei Dai who Satoshi only cited because Adam Back suggested that he do so.

Of the six remaining references, the most exotic one is the paper published in “20th Symposium on Information Theory in the Benelux” called Design of a secure timestamping service with minimal trust requirements that was published in May 1999. It was purportedly such a rare book that it had only been available in print to the 40 or so people who attended the obscure European symposium that year. Naturally, internet sleuths have used this knowledge to narrow down the likelihood that Satoshi was one of the very few to attend it in person and have frequently concluded that the answer to the mystery then is that Satoshi was the well-known cryptographer Len Sassaman. The evidence for this is an unusual photo of Sassaman’s bookshelf that was posted to his Flickr account in 2007. It’s a hardcover copy of a book from that very symposium. Unfortunately for this theory it’s not the right year because it’s of the 23rd symposium in 2002 and that paper that Satoshi referenced wasn’t in it. Despite this, it’s still used as circumstantial evidence that Sassaman, who died in July 2011 by suicide shortly after Satoshi’s disappearance (also circumstantial evidence that’s relied upon), was close enough to the circle of folks that attended that event that he would’ve had access to that book.

One major problem with this theory is that Satoshi Nakamoto appeared to have no idea what pages of the book the paper was on. Of the six references in question, it is only one of two for which no page numbers are listed. An academic would not have made the mistake of forgetting the pages (more on that later). Three of the references that Design of a secure timestamping service with minimal trust requirements cites are also papers that Satoshi cites, however, which has been used to bolster the argument that Satoshi did in fact have this book and that it’s what led him to cite the other papers. But that can’t be, or at least is very unlikely because how Satoshi cited these references materially differs from how that paper cited them. They use different dates, pages, and spelling, despite each being a reference to the exact same pieces of work. For example, the paper cites Improving the efficiency and reliability of digital timestamping as being published in 1992 while the Bitcoin White Paper asserts it was 1993. It cites the How to time-stamp a digital document paper as being on pages 99-112 of a journal while the Bitcoin White Paper asserts it was on pages 99-111. And the authors have a slight typo in the name of the book when they cite where the Secure names for bit-strings paper is listed in when Satoshi does not make the same mistake.

Perhaps this is all evidence that Satoshi was extremely diligent and made these changes manually or what is more likely based on additional evidence that will follow, Satoshi’s references were copied from another source, one that cited the same works and in the exact same way.

Below is a list of the references in the Bitcoin White Paper followed by a table showing how Satoshi cited the relevant references in the first column while the following columns are how those papers cited the same pieces of work, so long as they had them in their references too.

| Bitcoin White Paper | [2] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [7] | 8 |

| H. Massias, X.S. Avila, and J.-J. Quisquater, “Design of a secure timestamping service with minimal trust requirements,” In 20th Symposium on Information Theory in the Benelux, May 1999. |

||||||

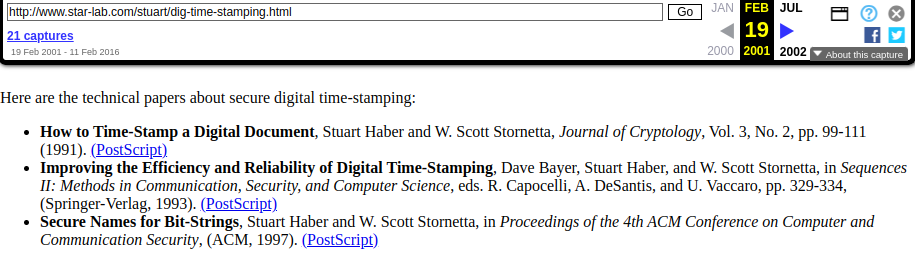

| S. Haber, W.S. Stornetta, “How to time-stamp a digital document,” In Journal of Cryptology, vol 3, no 2, pages 99-111, 1991. | S. Haber and W.-S. Stornetta. How to timestamp a digital document. Journal of Cryptology, 3(2):99-112, 1991. | S. Haber, W. S. Stornetta, How to time-stamp a digital document, Journal of Cryptography, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 99–111 (1991). | S. Haber and W.S. Stornetta. How to timestamp a digital document. Journal of Cryptology, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 99-111 (1991). | |||

| D. Bayer, S. Haber, W.S. Stornetta, “Improving the efficiency and reliability of digital time-stamping,” In Sequences II: Methods in Communication, Security and Computer Science, pages 329-334, 1993. | D. Bayer, S. Haber, and W.-S. Stornetta. Improving the efficiency and reliability of digital timestamping. In Springer Verlag, editor, Sequences’91: Methods in Communication, Security, and Computer Science, pages 329-334, 1992 | D. Bayer, S. Haber, and W.S. Stornetta. Improving the efficiency and reliability of digital time-stamping. In Sequences II: Methods in Communication, Security, and Computer Science, ed. R.M. Capocelli, A. Desantis, U. Vaccaro, pp. 329-334, Springer-Verlag, New York (1993). | ||||

| S. Haber, W.S. Stornetta, “Secure names for bit-strings,” In Proceedings of the 4th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, pages 28-35, April 1997. | S. Haber and W.S. Stornetta. Secure names for bit-strings. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM Conference on Computer and Communication Security, pages 28-35. ACM Press, April 1997. | |||||

| R.C. Merkle, “Protocols for public key cryptosystems,” In Proc. 1980 Symposium on Security and Privacy, IEEE Computer Society, pages 122-133, April 1980. | R. C. Merkle, Protocols for public key cryptosystems. In Proc. 1980 Symp. on Security and Privacy, IEEE Computer Society, pp. 122–133 (Apr. 1980). |

R.C. Merkle. Protocols for public key cryptosystems. In Proc. 1980 Symposium on Security and Privacy, IEEE Computer Society, pp. 122-133 (April 1980). | ||||

| W. Feller, “An introduction to probability theory and its applications,” 1957. |

What we can see now is that column two, the paper from the Symposium in the Benelux, indeed cites three of the same papers that the Bitcoin White Paper does, but it does it differently in each case. The closest match is reference #5, from a paper called Secure names for bit-strings from in “Proceedings of the 4th ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security” from 1997. If Satoshi had used any one paper as his primary source for the rest, it is this one.

Just as with the Benelux paper, Satoshi lists no pages for reference #8 for an old 1957 book about probability theory, which seems to be used as a blanket reference just to have something referencing probability in general. Odds are he did not have this book either. Satoshi was able to discern page numbers from the rest not because he had every one of these books but because the one that he did have, cited page numbers to the other books in their references and he merely copied them.

Broken down again is as follows:

Reference #2 cites #3,#4,#5

Reference #3 cites none

Reference #4 cites #3,#7

Reference #5 cites #3,#4,#7

Reference #7 cites none

Reference #8 cites none

With reference #5 being the most likely material that Satoshi had access to, he would have been able to rely on this alone to cite itself, #3,#4, and number #7 with deadpan accuracy. That’s four out of the six in question. #8, as mentioned before, was a throwaway while #2 looks increasingly suspicious as an outlier meant to obscure the one true primary source that Satoshi had access to. Because if there really was a link between Satoshi’s real identity and the ACM Conference (which took place in Zurich) in 1997, then mixing in an obscure symposium in the Benelux and citing it as the first real research paper in the White Paper would have and indeed actually has successfully thrown researchers off the scent. This despite Satoshi indicating he didn’t even know what pages the paper was on.

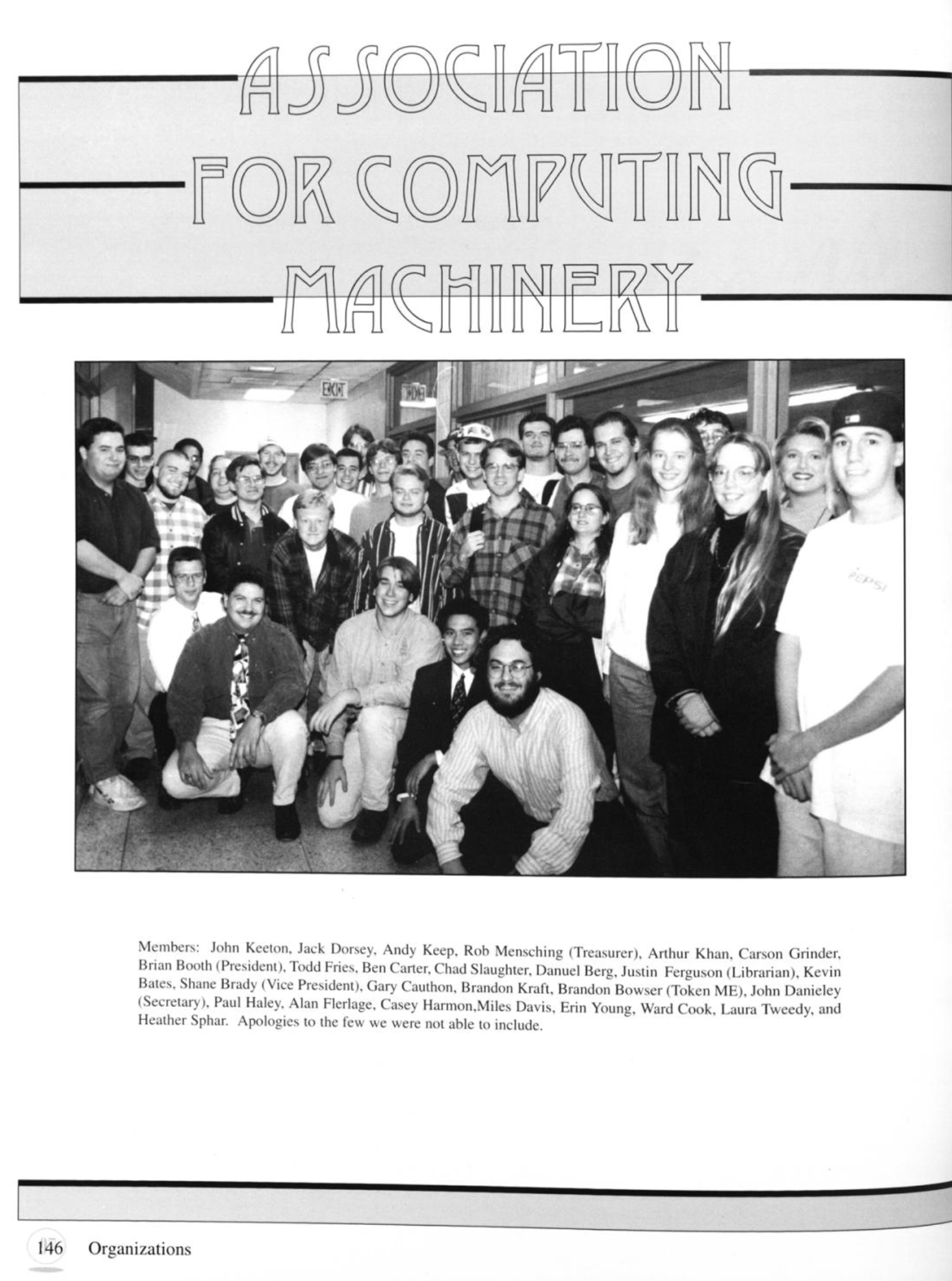

Looking closer now at #5 and ACM, which stands for Association for Computing Machinery, it’s a computing association that was founded in New York City in 1947 and has since grown worldwide. If ever there was a Satoshi candidate to consider that had a relationship with the ACM in ~1997 it’s none other than Jack Dorsey who sported a [email protected] email address for himself on his digital business card at least as early as November 1999. He’s since also been confirmed as a member of ACM in precisely the year of 1997 thanks to a yearbook photo taken at the University of Missouri-Rolla in 1997 and official membership archives. See below:

According to the ACM website in 1998, it said that “As a free benefit of membership, ACM is now offering all members individual e-mail addresses @acm.org. […] The username of your account is also your acm.org e-mail handle (or alias). Mail sent to your [email protected] will be forwarded to your real e-mail address.”

Memberships had to be paid for. (Student pricing at Dorsey’s school)

Jack continued to publicize that email address for himself at least through October 2000 before he completely overhauled his blog and no longer shared that information.

The ACM digital library makes thousands of research papers available to access digitally (which began in 1997), including the aforementioned 5th reference Secure names for bit-strings. The Symposium in the Benelux one cannot be accessed and is not in the library.

Jack Dorsey’s connection goes deeper than just having clearly been a member of the ACM a decade before the White Paper came out. It’s previously been publicized that Jack began working as a programmer in digital publishing in 1991 at a company called Mira Digital Publishing. Not only does the modern day website state just how important Jack was to launching that company’s first product in 1992 but it also credits him with pivoting the company into conference content in 1996.

“With the World Wide Web explosion in the 1990’s, Mira shifted from tradeshow content to conference publishing, and in 1996 released one of the first commercial systems for online abstract submission management and peer review,” the website states as of this writing.

Mira, coincidentally, focused on publishing research papers from conferences “with help from Jack Dorsey” where authors had to submit their research papers directly to Mira. Some of Mira’s clients were societies within the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), which had developed a global presence. “[B]y the early 21st century, IEEE served its members and their interests with 39 Societies; 130 journals, transactions, and magazines; more than 300 conferences annually; and 900 active standards,” the main website stated.

See some examples of Mira and IEEE here: (1, 2, 3,)

IEEE societies still work with Mira today. IEEE is so big that one of Satoshi’s references, #7, was of R.C. Merkle from an IEEE event in 1980. Even more notable, however, is that IEEE was the publisher for a paper that was co-authored by the same three authors that wrote the Benelux paper on the very same subject. Titled Timestamps: main issues on their use and implementation by H. Massias; X. Serret Avila; J.-J. Quisquater, they submitted this paper to an IEEE Workshop in June 1999 and cited their submission to the Benelux Symposium the month before in their references. The IEEE submitted version citing the Benelux paper is available on the IEEE site while the actual Benelux version is not. As we know, Satoshi didn’t actually have the Benelux book since he didn’t know what pages the paper was on, only the citation information, which matches the IEEE paper and would’ve been accessible in 2008.

These events are not borne out of a coincidence where ancient history is attempted to stitch together events that took place a decade later. Mira’s owner, for example, Jim McKelvey, was still collaborating with Jack Dorsey a decade later in 2008 and the two co-founded Square (now Block) together in 2009, all while McKelvey was still running Mira. Jack was literally business partners with the owner of Mira during the time in question.

Authors submitting research papers through the Mira software were told to use common applications like “Word, WordPerfect, PowerPoint, Freelance, LaTex, etc.” for their work in the early years and in the present day advise they be in “PDF, Word, Pages, LaTex, PowerPoint, etc or even the occasional Word Perfect format.” They also said their real power was flexibility. “We know you have your own unique process, and we’re happy to mold our system to your needs – whether it be branding, dual author affiliations, author disclosures, or anything else. Our experienced staff has seen just about everything, and we’re not afraid to customize.”

Satoshi, meanwhile, seemed to go out of his way to use OpenOffice, a feature that became the subject of much debate in the COPA v. Craig Wright trial over the identity of Satoshi Nakamoto. It was notable in that it was NOT LaTex or something more commonly used for such a paper, which again could suggest that Satoshi was trying to distance himself from something that would’ve connected to his real identity. While one can’t say with 100% certainty where Satoshi drew his sources from, Jack Dorsey’s experience in the research paper software business is a rather striking and relevant detail to the possibility that he is Satoshi Nakamoto. After all, if among the possible candidates to be the author of a white paper, should one that was specifically in the “white paper” submission and distribution business with demonstrable knowledge of or access to the primary source(s) used in the paper be critical information? I believe that it is.

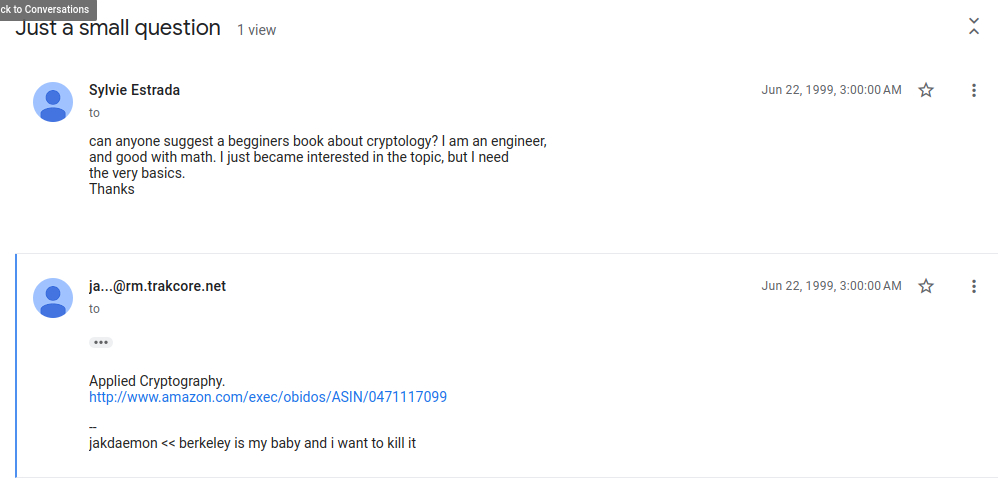

Notably, Jack Dorsey would’ve encountered some of the authors of these papers another way. In June 1999, he actually advised someone to read Applied Cryptography: Protocols, Algorithms, and Source Code in C by Bruce Schneier. Schneier was famous with the cypherpunks because he designed the Solitaire encryption algorithm in Cryptonomicon authored by Neal Stephenson, and Jack knew about it. The Bitcoin White Paper was released on 10/31, Stephenson’s birthday. Jack is also confirmed to have been on the cypherpunk mailing list himself.

Like the Sassaman bookshelf theory above, we can assume that this Applied Cryptography book actually sat on Jack’s bookshelf. That book also cites Merkle, Quisquater, Bayer, Haber, and Stornetta, just like Satoshi does, and even uses two of the exact same references in its bibliography that Satoshi uses in his Bitcoin White Paper. Alas, Schneier cites them the same way as the Benelux paper does (with a different page number on one and a different year on another) rather than the way Satoshi and reference #5 in Secure names for bit-strings did.

Suffice to say that the Bit-strings paper from the 4th ACM Conference remains to be the prime suspect as the original source for Satoshi in the White Paper regardless of who Satoshi was. Suspiciously, this term was one that another Satoshi candidate, Nick Szabo, wrote about in April 2008 (which he since changed the publication date for), to build on his 2005 idea called Bit Gold. “Bit strings (puzzle problem/solution pairs) are securely timestamped by their time of publication,” he said. Szabo even linked out to a cryptography resource portal in that 2005 paper which also references three of the same sources that Satoshi did and in a manner similar to how Satoshi cited them but not exact. Szabo’s source didn’t know the pages that the Bit-strings paper was on in the ACM Conference book. So Satoshi got it right but Szabo’s source didn’t.

In the comments of Szabo’s own April 2008 post he extended an open invitation to help him code up something like Bit Gold using bit strings. If Szabo is not Satoshi (which he has emphatically denied being), then Satoshi had possibly read this blog post in April 2008 and took up the challenge despite not crediting him in the Bitcoin White Paper. Advocates of the Szabo-is-Satoshi theory point to the omission of Szabo as evidence that it was Szabo. However, this theory is weakened by the possibility that Adam Back could have just as easily told Satoshi to cite Szabo in addition to Dai. Satoshi did not hesitate to take Back up on his suggestion to email Dai and cite him in his paper. Likewise Dai could’ve also told Satoshi to cite Szabo but he didn’t either. So even though both Back and Dai would later in retrospect say that Szabo was one of the very few people capable (Dai says Szabo is not Satoshi) of being Satoshi, when they were actually sent the White Paper from Satoshi, neither thought of him at the time. In any case, Satoshi communicated to Back that his system combined “proof-of-work to support a distributed timestamp server” a system he could’ve arrived at on his own without ever having encountered writings by Szabo. Indeed when getting back to those fundamentals, we revert back to the papers cited in “Secure names for bit-strings” and combine them with Adam Back’s ideas.

As it turns out if Satoshi had continued to follow ACM’s annual papers, he would’ve encountered Hashcash at the proper time period in question regardless. That’s because from October 29 to November 2, 2007, this very same conference, the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security, held in Alexandria, VA that year, had multiple papers citing Adam Back (Out of 55 total that were published. 302 papers were submitted). One paper published that cited Adam Back’s Hashcash is titled Harvesting verifiable challenges from oblivious online sources. It explores proof-of-work challenges provided from oblivious sources as an alternative to two-way-street peer-to-peer systems. It makes multiple references to Hashcash in that regard. Besides the fact that it was published by respected computer science professors, it also adds a touch of conspiratorial flair in that it discloses that the research was supported by the Department of Homeland Security and the US Army Research Office. It also links to open-source software that the authors wrote in Python that implements it (today it’s deleted). So it was not just a theory, but actual working software.

Another paper published at the conference citing Adam Back was called Filtering spam with behavioral blacklisting.

Suffice to say that outside the recurring cast of cypherpunk characters and Satoshi suspects there were other researchers pondering similar questions. The ACM conference had even been promoted on July 13, 2007 on the same metzdowd cryptography mailing list that Satoshi released his White Paper on.

Satoshi is supposed to have started on his work somewhere around these times. He told Martti Malmi, for example, that he had started developing Bitcoin in ~January 2008 while telling James A. Donald that it was ~May 2007, making him an unreliable narrator perhaps. Still, the idea that Adam Back’s 1997/2002 Hashcash invention was limited to roughly the knowledge of four people capable of combining it with other features ignores just how much wider the pool of capable and knowledgeable candidates is. For example, 277 people attended the ACM conference in 2007 and would’ve been able to watch the in-person presentation on proof-of-work. That’s in addition to all the ACM members that would’ve gotten access to the paper and still more the rest of the world who could access it online for free. Not to mention that Jean-Jacques Quisquater, one of the authors of the notorious Benelux paper, was not only in attendance but presenting!

The conference in 2008 was again held in Alexandria, and it coincidentally concluded on October 31, 2008, the date the Bitcoin White Paper was released. Although I’ve pointed out that this is cypherpunk author Neal Stephenson’s birthday, this occurrence does time neatly if Satoshi had hoped to piggyback off the momentum of that particular conference. A Session Chairman of that conference, for example, Michael K. Reiter, had just authored a paper a year earlier citing Adam Back’s Hashcash.

If Satoshi had seen any papers citing Adam Back, which he must have if Hashcash was such an instrumental component to his idea, then it stands to reason he would not have had to e-mail Adam Back and ask him if his citation style was correct. Dozens of people and papers were regularly citing Back and the format was widely available. Instead, Satoshi most likely used that as an excuse to strike up a conversation with Back. Indeed, he invites Adam Back to download a pre-release of his paper and to “feel free to forward it to anyone else” he thought would be interested. He also tells him that he’s almost done with a C++ implementation to release as open source. Satoshi, therefore, was trying to build up interest in his work with the person he thought would find it most compelling. Satoshi may have even been a fan of his. In subsequent emails Satoshi continues his pitch to Back but does not get the enthusiasm he hoped for in response since Back said he didn’t even read it.

Finally, Satoshi’s citations are a bit weak. There’s not that many of them and it’s not always clear what he’s referencing when he’s making a reference other than to indicate that his work is rooted in other works broadly speaking. For two of his six major references, he omits the page numbers, an inconsistency which likely means he was not an academic like many theorize. On this we revisit a comment Satoshi made to Martti Malmi on May 4, 2009 when he said that he had been performative.

“The site at bitcoin.org was designed in a more professorial style when I was presenting the design paper on the Cryptography list, but we’re moving on from that phase,” Satoshi wrote to Malmi. Satoshi, therefore, was self conscious about the initial audience he was catering to. While Jack Dorsey was not an academic himself, it was well within his wheelhouse to act professorial when releasing a research paper. He’d seen them done a million times.